From the 11th to the 16th century, royal weddings remained very private affairs, but as the powers of the monarchy declined and Britain began a transition to a modern system of government, old barriers were broken down. A flourishing print culture stimulated an appetite for royal weddings, and popular accounts of weddings in this period are supplemented with commemorative medallions, tokens and novelty items that we would recognise today; conceptions of royal marriage were beginning to change in the popular imagination, and become something that the public had an emotional stake in, however slight.

Entering into the late post-Medieval and modern period, much more evidence for royal weddings survives, as mass produced souvenirs entered the archaeological record. Just such a find was made by a metal detectorist Marie Hunt in a field near Owestry, Shropshire, in July 2010. She found a group of silver coins, which were unusual in that they included a silver gilt medal commemorating the 1625 marriage of Charles I to the French princess Henrietta Maria.

The head of the medal depicts the portraits of Charles I and Henrietta Maria, under rays from heaven, whereas the reverse shows Cupid with flowers and references the union of the roses of England and lilies of France. The inscription is a modified quote from Virgil’s Aeneid, FVNDIT .AMOR. LILIA. MIXTA. ROSIS./.1625. (Love pours out lilies mingled with roses). The medal was found with six other coins with varied wear and clipping, suggesting that they were come from a single body of material deposited on one occasion, probably in the early 1630s.

They consisted of two sixpences of Elizabeth I, two pennies of James I and two pennies of Charles I. The wear and clipping visible on the coins of Elizabeth makes it probable that they had experienced considerable currency, which would certainly be compatible with the idea that they represent 17th century deposits. Medals are not usually found with coins in this way, but given that the other coins had experienced considerable currency, it is possible that this one served as a pocket piece. It could have been carried around for luck, as a symbol of loyalty or as even a marital memento.

Royal Wedding Venues

When it comes to wedding venues, there seems to be only one of two choices for today’s self-respecting British royal: Westminster Abbey or St. Paul’s Cathedral. Westminster Abbey has certainly been the location of many royal weddings (14 in total) but it is worth remembering that no royal nuptials took place there between 1382 and 1919 – over 500 years of British history.

The return to Westminster in the 20th century, as well as Charles and Diana’s decision to break with previous tradition and wed in St Paul’s Cathedral, has much to do with fitting more guests in, highlighting the trend for treating Royal weddings as monumental public occasions.

The return to Westminster in the 20th century, as well as Charles and Diana’s decision to break with previous tradition and wed in St Paul’s Cathedral, has much to do with fitting more guests in, highlighting the trend for treating Royal weddings as monumental public occasions.

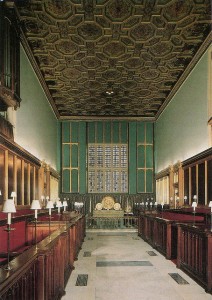

However, there was another venue that was much in vogue in years past: The Chapel Royal at St James’ Palace. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, a flock of royals tied the knot in there, including Prince Fredrick and Augusta in 1736, and Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1839 – their wedding certificate, signed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, today hangs on the wall in the vestry.

The Chapel Royal at St. James’s Palace was constructed by Henry VIII, and decorated by Hans Holbein in honour of the king’s short-lived marriage to Anne of Cleves. If the Chapel Royal at Greenwich can be said to be at the heart of the Royal palace, then the Chapel Royal at St James’ Palace has a heart all of its own: when Queen Mary I died there in 1558, her body was taken for burial at Westminster Cathedral, but her heart and bowels were buried beneath the choir stalls, and there they remain to this day.

Conclusion

If the last thousand years of history was wiped clean, and all we had to go on was the artefacts, objects and scattered sites to inform us about royal weddings, we would unfortunately know very little. But taken together with the long view of history, the buildings and objects that archaeology reveals give an appreciation of the human scale of these royal events. Looking back through the centuries, we can see that royal weddings have changed significantly; from small, private ceremonies with little personal feeling in the Medieval period, to the large State occasions of the last century, where private feelings are front and centre. Having met outside of royal circles and enjoyed a long courtship, William and Kate epitomise just how far the public’s expectations have travelled. Rather than a political union for the benefit of the country, we now expect that first and foremost, a royal marriage should be a love match: the fairytale wedding in full bloom. Reflecting on another commoner’s path to the royal household through the Medieval forests of Northamptonshire, it seems that history really does repeat itself after all.

Download the full article here…

Subscribe to Current Archaeology here…