Teaching would be great if it weren’t for the kids; parliament even better if it weren’t for the voters; and commercial archaeology, or so the joke around the site hut goes, would be the best job in the world if it weren’t for the clients. With no clients, there would be no project managers, and with no project managers, there would be no competitive tendering, and with no competitive tendering we could all live happily ever after in the land of milk and honey.

Competitive tendering – the process by which archaeologists bid against each other in order to win projects – has long been blamed for everything that is wrong about archaeology, from poor pay and conditions to the assassination of JFK. In the wider economy competition is usually considered to be a healthy stimulus to growth, driving honest-to-god entrepreneurs to innovate, take risks, and work hard.

Competitive tendering – the process by which archaeologists bid against each other in order to win projects – has long been blamed for everything that is wrong about archaeology, from poor pay and conditions to the assassination of JFK. In the wider economy competition is usually considered to be a healthy stimulus to growth, driving honest-to-god entrepreneurs to innovate, take risks, and work hard.

But for archaeological field workers living on bread-line wages in bed and breakfast housing, competition merely explains the downward pressure on pay and conditions. At best, woefully incompetent; at worst, wilfully complicit; their project managers seem intent on submitting lower and lower prices, cutting each other’s throats in a race to the bottom.

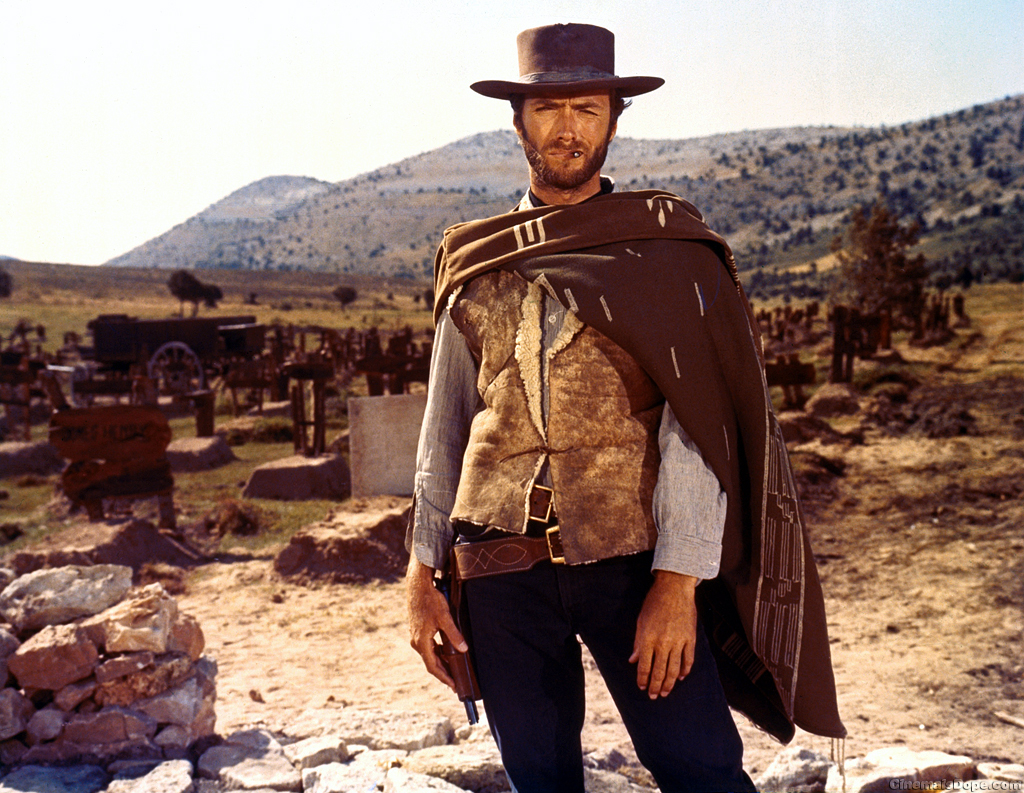

A fist full of dollars

But this overly simplistic view fails to grasp the basic economics of commercial archaeology – and there have been three highly significant developments this year that call for a rethink on the fundamental economic realities of the heritage market.

• The first is the replacement of Planning Policy Guidance 16 (PPG16) – the planning document that has underpinned the archaeology market for the last 20 years – with Planning Policy Statement 5 (PPS5).

• The second is the move towards Chartered status by the Institute for Archaeologists – the body representing the interests of professional archaeologists – with an initial consultation to its membership.

• The third is the merger recently announced by two of the largest archaeology companies in Britain to create one of the largest archaeological companies in Europe.

Set against the deafening noise of one of the deepest recessions in history, it’s not entirely clear to fieldworkers whether commercial archaeology is maturing as a discipline or sinking into terminal decline. My contention is that these three developments are game changing moves, but to understand why we need to go back to the beginning and ask: how exactly was the west won by commercial archaeology?

The Wild West

Emerging from post war reconstruction into the half-light of a free market dawn, archaeology became part of the planning process in a non-voluntary manner, swept along with other environmental concerns that sought to balance the impact of development on third parties. By making archaeological investigation a necessary step to being awarded planning permission, PPG 16 shifted the burden of cost from the public purse to private enterprise, and the benefits were far reaching.

A new and uncharted territory was created – a wild-west frontier – where funding decisions were no longer the whim of shortsighted politicians. An archaeological land grab ensued as county council units, charitable trusts and private companies competed in open tender to be granted the opportunity by developers to excavate sites. Some organisations have been very successful at this game, outgrowing their regional origins to become multi-million pound international businesses. But others have dramatically fallen, and concerns about cost cutting and the necessary effect on the quality of archaeological work undertaken by commercial organisations are periodically raised.

A new and uncharted territory was created – a wild-west frontier – where funding decisions were no longer the whim of shortsighted politicians. An archaeological land grab ensued as county council units, charitable trusts and private companies competed in open tender to be granted the opportunity by developers to excavate sites. Some organisations have been very successful at this game, outgrowing their regional origins to become multi-million pound international businesses. But others have dramatically fallen, and concerns about cost cutting and the necessary effect on the quality of archaeological work undertaken by commercial organisations are periodically raised.

With word coming in from the trenches that poverty stricken field archaeologists have been forced to make ends meet by taking in ironing (and as yet unconfirmed rumours that others have been performing happy ending massages) it’s worth taking stock of the current market condition. In an archaeological transaction, what is it exactly that the developer is purchasing?

The good

Reduced to its basic economic algebra, commercial archaeology inhabits a particularly hostile business environment. A good, in economic terms, is defined as a physical, tangible product that can be delivered to a buyer (such as a pair of scissors) as opposed to a service (such as a haircut) where ultimate ownership isn’t exchanged between the two parties. Commercial archaeology similarly trades as a ‘service’, solving the needs of its customers to discharge a planning condition. The tangible product of this work – the site reports, archive or published papers – cannot be regarded as a ‘good’ in an economic sense, as there is no transfer of ownership of these products.

Reduced to its basic economic algebra, commercial archaeology inhabits a particularly hostile business environment. A good, in economic terms, is defined as a physical, tangible product that can be delivered to a buyer (such as a pair of scissors) as opposed to a service (such as a haircut) where ultimate ownership isn’t exchanged between the two parties. Commercial archaeology similarly trades as a ‘service’, solving the needs of its customers to discharge a planning condition. The tangible product of this work – the site reports, archive or published papers – cannot be regarded as a ‘good’ in an economic sense, as there is no transfer of ownership of these products.

The bad

Rather than think of archaeology as a ‘good’, it might be more beneficial to think of archaeology as a ‘bad’, defined in this instance as any good with a negative value to the consumer. Archaeology is rubbish, and although we derive great satisfaction in trying to understand how this material culture relates to the people who made it, it’s worth remembering that to our clients, archaeology really is rubbish. It is the contaminated detritus of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years of human activity. Archaeology lowers the utility value of the land for future development, and commercial heritage workers are paid to take it away, or advise a cheaper course of action that preserves the remains in-situ.

The ugly

The great mistake of the PPG16 revolution was to assume that all that was needed to make it work was free, lightly regulated and flexible markets, and that institutions imposing ethics, transparency, and accountability got in the way. Any measures to help the Sherriff stop the cowboys being, well, cowboys, have been consistently undermined by no one really knowing who the Sherriff actually is. The IfA? Prospect? The County Council? English Heritage?

This situation is further complicated by the ambiguity surrounding what exactly constitutes ‘quality’ in commercial archaeology. A quality archaeological product (generating new, secure, and accessible knowledge of the past) is not necessarily the same thing as quality management of archaeology (managing a program of archaeological work within time and budget). The two are far from mutually exclusive, but the fact remains that an archaeological business can trade on an exceptional reputation in the construction industry, whilst simultaneously producing poor quality results for the archaeological community.

For a few dollars more

As Martin Carver recently argued, the only reasonable way forward for commercial archaeology is to rewrite the rulebook, changing the nature of competition in the heritage market from a ‘lowest price wins’ to a ‘best project design’ contest – a model closer to that practiced in architecture. The unbridled reign of the market has turned archaeological knowledge into an ‘externality’, or spill over effect, as archaeologists compete to secure planning permission for their clients as cost-effectively as possible. So what would be needed to affect the type of changes advocated for above?

Back now to the three important new developments mentioned at the outset, followed by an explanation (and apology) for my Wild West conceit.

Firstly we would need a collaborative planning regime that enables archaeologists to design strategies that generate both archaeological insight and commercial advantage for their clients (PPS 5). The new document sets the historic environment alongside other competing planning concerns, moving away from a tick-box culture of compliance and enabling commercial archaeologists to propose practical and cost effective solutions.

Secondly we need to restore trust in competitive spirit by barring the archaeology market to all but the suitably qualified and experienced (a fully chartered Institute). By placing the choice of who does or doesn’t practice as an archaeologist entirely in the hands of those who don’t want to pay for it, the current system has seen a steady dismantling of trust, pitting field archaeologist against council archaeologist in an adversarial system. This proposal is only at consultation stage, but it is the first step to awarding charted status to individuals, and putting the necessary architecture in place to rigorously enforce standards.

Thirdly we need to cultivate a healthy business environment in which archaeology is no longer perceived as a last minute distress purchase. The ‘point’ of archaeology has been disentangled from its ‘purpose’, but by building strategic relationships with clients and stakeholders, commercial businesses can recombine the two. Archaeologists should be involved with their clients management teams from the earliest opportunity in the development cycle – managing risk, minimising impact (and associated costs), and maximising the knowledge yield from any cultural heritage intervention.

Whether the proposed merger between two of the biggest units will address this remains to be seen, but along with other companies that are seeking to regionalise their operations and reposition their services, it demonstrates an ambition to offer the market more than just another ‘stack it high, sell it cheap’ option.

The End (of the beginning)

Set in the American Old West in the mid 19th century, the western glamorised a frontiers world that was already long vanished by the time the genre became popular. Archaeology has similarly passed through a wild-west stage, colonising a largely hostile market place in the name of knowledge and the public good. But its time to bid the cowboys farewell: this town aint big enough for the two of us. Their gun-slinging ways make for a ripping yarn, but god knows you wouldn’t want to live there.

Old archaeologists never die, their cortex just becomes friable!

Slightly off message there Gary but not to worry – one liners are always welcome round these parts!

England, and Ireland for that matter, have made it quite easy for themselves to deal with archaeology. Their policy spells let someone else deal with it (commercial archaeologists) and let someone else pay for it (developers), hoping that greed and the extreme cost cutting wouldn’t get the better of the two involved. And while the government saves itself a lot of money and hassle, the developers get their planning permission for as little money as possible and the commercial archaeology companies making the big buck, the poor sods in the field as well as the archaeology itself are being ripped of and violated. The pressure on site to deal with the archaeology within the way too narrow time frame and budget has left archaeology been deliberately dug through or poorly resolved by graduate archaeologists who get paid less than an untrained burger flipper at Micky D’s. Worse, me and colleagues have been working on sites under such poor conditions that we were tempted call Amnesty International for help. No shelter in the middle of a swamp in the midst of winter, general lack of facilities and tools and cornered by grumpy land owners, pushy developers and greedy employers the job has simply become unbearable.

The submissive butt-kissing attitude of so many archaeologists, However, has made these circumstances possible, so we shouldn’t complain. It’s home made.

I don’t know what the British Institute of Archaeologists is like but here in Ireland I will not trust our IAI (Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland) as it is mostly made up of owners of commercial archaeological consultancies and I fear that they don’t really care too much about the interests of their field workers, especially if it eats into their own profits.

That leaves the diggers pretty much without a public voice and since work got pretty sparse these days, no one is willing to raise their voice out of fear to be blacklisted by the companies.

A reform of how archaeology is being dealt with in Ireland and England needs to be from bottom up, beginning with a union specifically for the field workers and not the bosses. Furthermore, excavations should be closely monitored by external and independent professionals and thirdly, directors should not be employed by consultants but either by the local authorities or hired from a college or university, being accountable only to those. This way highest standards and a fair treatment for everyone can be guaranteed.

Everybody is entitled to their opinion about whether archaeology is rubbish or not, bottom line is, that there is European legislation and other commitments (Valetta Convention etc.) that are to be adhered to. This is not the case. Everybody in the profession knows that but no one has the guts or the motivation to do something about this.

Dig This, welcome, and thanks for shooting the shit.

So this is what you see as the problem:

• A passive state, greedy employer, disinterested client, compliant work force.

This is what you see as the result:

• A collapse in standards, as well as pay and conditions (especially in line with untrained manual workers like burger flippers).

This is what you see as the solution:

• Unionize the workforce to protect and further the rights of those at the bottom.

• Bring the commercial sector into state ownership – either directly employed by the council or by universities.

• Rigorously enforce standards with an independent body of professionals.

That’s certainly one vision, and though we agree that things are less than rosy in the archaeological garden of Eden, it’s pretty much the exact opposite of the case for change made above. As Winston Churchill once remarked, ‘Capitalism is the worst possible way of organising society; apart from all the other forms that have been tried from time to time throughout our history.’

There are some compelling arguments for why your ‘bottom-up’ model won’t work for archaeology… but I think I’ll let some other sharp-shooters come in before I unleash the Smith and Weston…

I agree wholeheartedly with the need to change the perception of archaeology but I think there is a deeper issue which needs to be considered. Your piece makes a basic assumption, one which I find myself wrestling with, the assumption that archaeology is valuable and how it is valuable. I would just like to take a step back and look at the archaeology market form a slightly different perspective.

On way one look at it is that a Market for archaeology exists because PPS5 (and PPG16 before) translates / transforms the true value of archaeology into something which works in the current market economy – but it’s an imperfect translation – it loses something of the true meaning and value of archaeology in the process, and the way archaeology is practiced has changed in light of this.

It is essential to remember that this economic value system is artificial and ‘downstream’ of the true value of archaeology. By focussing on the economic value I think we may be in danger of missing the point and to continue the river analogy in danger of choking off the headwaters.

I am a little wary of this statement in your piece.

‘we need to restore trust in competitive spirit by barring the archaeology market to all but the suitably qualified and experienced’

I appreciate what you are talking about is the archaeology market – but what’s being traded is the past and it doesn’t belong to professional archaeologists, it’s not ours or the developers or the IFA’s to ‘bar’ people from – You have assumed that because professional archaeologists are suitably qualified and experienced in the economic market of archaeology then that is adequate, and it may well be but we need to demonstrate that, we need to demonstrate that what we do actually appeals to those upstream values. Something I believe we have failed to do.

To take your Wild West analogy a little further its worth remembering that the west was actually won by killing tens of millions of native Americans and destroying a largely misunderstood existing culture and value system and replacing it with something which has at least as many problems as any other system, all in the name of free market capitalism.

This is not JUST high minded philosophy (in fact it’s not high minded philosophy) there is a practical aspect. When the ConDem government push through there cuts and everyone is fighting their corner we are going to need to demonstrate the true value of archaeology and the true value of archaeology is not clearing Planning Condition no 4 for Hamburger Homes, That is just a way archaeology has been forced to function and it’s not ideal. The true value is way upstream form that and we need to try to re connect what we do with those values otherwise people will stop caring and stop fighting for heritage and even worse what we do becomes pointless and I really don’t like that Idea!

Its worth noting one of Winston Churchill’s slightly better know quotes 🙂

‘……democracy is the worst form of government except all the others ‘that have been tried’

Thanks Tiny Bitgreen – nice angle! Didn’t see that one coming (think it ricocheted in off the church bell!). This is a really interesting question – what we in the business call a five-pinter.

Is archaeology valuable and if so how valuable?

For the purposes of this article, I have assumed that gunfight was won some time ago, and concentrated on the economics of the system we have inherited. The ‘true value’ of archaeology that you allude to, transformed through the planning process and thus losing some essential essence in translation, is a strong argument. In philosophy and art it calls to mind debates concerning the independence of the aesthetic. Can art, music or literature be both commercially successful and still maintain artistic integrity? Can archaeology be both commercially successful and still maintain archaeological integrity?

In later posts I may yet tackle the politics of commercial archaeology, addressing the broader point you have raised about value, and concomitantly, its reason and basis. But for now I’ll deal with your supplementary points.

1. You write that you are wary of my statement that “we need to restore trust in competitive spirit by barring the archaeology market to all but the suitably qualified and experienced.”

That’s not the same as saying we should bar people from the past, or that because we are professionals we ‘own’ the past and have no duty to communicate what we do with the wider world. Just as your health doesn’t belong to your physician, you would still hope that they had passed all their exams, and had a demonstrable track record in medicine before they were allowed to practice on you. So too with archaeology.

2. I too am thoroughly mistrustful of the ConDem alliance, but their cuts are unlikely to directly affect commercial archaeology. The PPG revolution took care of that by removing our dependence on central funding, and wider European Legislation means that won’t be easily revoked. It may even open opportunities as councils seek to out-source their core responsibilities and services. The main threat is actually ideological – The Big Society – and I would argue that your ‘throw the doors open’ position plays directly into their hands. How soon before woolly sentiments to ‘empower local communities’ results in amateur societies undercutting professional units for small projects? Forgive me, but power to the people my arse.

3. Extended Metaphors are my meat and drink, but I have to confess to getting lost on your “its worth remembering that the west was actually won by killing tens of millions of native Americans and destroying a largely misunderstood existing culture.” I’m not sure where you were going with this, but I’d just like to reassure you that no Buffalo died in the creation of this blog post.

4. This blog post is a take on a number of changes that have happened this year or may yet happen over the next few years. It’s an answer to all the doomsayers, because I am at heart, a glass half full man. I know its half full, because I drank the first half personally, and it was bloody gorgeous!

On that note it’s worth finishing with one of Churchill’s even better known quotes.

“Oh Yes!!!”

Clint (did you know you have the same name as a famous actor?)

Thanks for taking the time to respond, I have some thoughts.

1, I appreciate your physician argument but it doesn’t entirely work for me. Most people can have a good stab at what the true values a physician’s work relates to (the pun was intended) and would broadly agree with them. This isn’t necessarily the case with archaeology:

Choosing a Physician

I value not being in unnecessary pain and not losing my life, therefore I would like a physician who is adequately trained and has a demonstrable track record in working towards these values.

Choosing an archaeologist in the commercial environment

I value having my planning permission as cheaply and efficiently as possible therefore I would like an archaeologist who is adequately trained and has a demonstrable track record in working towards these values.

I would suggest a more appropriate formulation and one that brings it in line with your physician analogy.

I value (the true values of archaeology) therefore I would like an archaeologist who is adequately trained and has a demonstrable track record in working towards these values.

2, I agree up to a point, but it will have a serious effect on English Heritage and local authority archaeologists. This reduction in capacity of the local authority archaeologists to argue in the face of competing political interests in planning departments may be seriously detrimental to us all.

I am a democrat at heart and don’t necessarily see that out sourcing capacity from a democratically elected body to business a good thing.

I think I made my point badly here – I do not advocate a ‘throw the doors open policy’ I advocate that archaeological work should be carried out in relation to the real value of archaeology not to economic values. If an independent group or academic archaeologist demonstrate abilities and qualifications in this respect then yes they have as much right as OxSex Archaeology (I wonder if that’s what stopped that particular merger?)

3, I was attempting and obviously failing to suggest that your metaphor was a little ironic – The ‘Wild West’ was built at the expense of an existing and competing value system. Free marketeers at the time branded this system as backward and believed it could be improved upon, this included ‘barring’ indigenous people from the process. We have since realised that this was done at the expense of something we would now see as valuable although not in economic terms.

It been a long day and I just cant think of a Churchill comeback.

Interesting article – Sort of.

I would like to know why anyone thinks archaeology is of any “useful” value.

What does an archeologist do that makes one bit of difference to the average guy on the street making a daily living?

I question where does any finding resulting from an archeologist work make a difference any anything in today’s working world?

Can anyone produce documentation or papers where one can find an actual “Return on Investment” on an archeological site?

Since it appears that no one even reads “written” history current or otherwise) to apply lessons learned in order not to repeat mistakes why would anyone think that archeological history is of value? Since most archeological work is “educational guess work” any way!

Just asking

I will answer this DWMACK…

But not tonight Josephine.

let you know when the post goes up.

your conceit is belaboured by your pieces misnomer (bet you cant say that the same twice on trot)as you should replace won with lost

otherwise shame it aint the smoking gun it should have been

To answer DWMACK’s comment on what is the ‘useful value’ of archaeology….

You could equally ask what is the ‘useful value’ of Aires rock, or mount Everest. What possible value could the ozone layer or a rain forest or a blue whale give (other than from their destruction).

Not everything valuable can be assigned a monetary value or an immediate return. Some things are just priceless.

But as to archaeology……cultural diversity is just as important as biodiversity. We just can’t see it at the moment.

Another important and immediate current use of archaeology is in politics, whether its to justify ethnic cleansing (In Bosnia, Albania and during the second world war), or in arguments of national identity (BNP, Israel, Lebanon etc).

Most of the human race find their ethnic background (their cultural heritage) very important as it defines who they are and where they came from. It gives them a history, a place in the world and a sense of pride in ‘their’ collective past.

You seem to be in the minority

Archaeology is the science from which questions about peoples past can be asked, and theories challenged. Hitler’s ‘airian culture’ theory can be disproved by archaeology.

Racist claims that native English people are only the ‘White Anglo-Saxon Prodestant’ is nonsense when faced with the archaeological evidence of thousands of years of immigration, changes in ethnic identity and multi-racial contact.

The combined evidence collected through archaeology is a vital dataset that is used in other disciplines including anthropology and medical science.

Recently I read a little news snippet of how scientists have used skeletons excavated during archaeological digs to study the history (going back 12 000 years or more) of cancer. You see for most scientific study a long dataset into the past is really useful in studying patterns and finding solutions/causes.

Archaeological information can also been used in anything from climatology, evolution, sociology etc etc etc. the list is endless (but space here isn’t)

I haven’t even touched on tourism…..

@Eli Wallace We may have collectively lost out overall (it remains to be seen how well the planning process will hold up the ravages of the current regime) but the west was won nontheless. That the commercial sector is by far the biggest employer of archaeologists is prima facie grounds for accepting this point.

@Jack Good set of points, with a whole bunch of well considered examples. I’m wondering whether DWMACK can be reasoned out of his current view point – if he was ever reasoned in there to begin with…

Meesta Wilkins

The PPG16 industry boomed and is busted. Its conceite was to create a market for a product nobody wanted. The National Planning Policy that is swinging in from the right like Tarzan in spandex, will spatchcock whats left. The shame is that even though the wall still drips dayglo paint the soldiers of PPG16 fortune will still be lined up against it. Prima facie that on Boot Hill.

Not sure I totally agree with you there cowboy.

Archaeology is not a product that ‘no body wants.’ The tenor of this piece is the nature of competition in the cultural heritage market, and the problems that follow when those who pay for the product have no other ‘buy-in’ apart from the requirement to discharge a planning condition.

In the best of times, developers are not necessarily immune to our aspirations as archaeologists, and value our commercial insight above our competitive rivals (i.e. competition can be good). In the worst of times, the market needs strong regulation, with barriers to entry at the very least.

On past form, we have about 2 more years of this recession left, after which it will be business as usual – as long as those Tarzan clad spatch-cocks don’t dismantle the only regulatory body we currently have – the council curatorial archaeologists.

Hey Kid

I’m not saying nobody wants archaeology, i’m just sayin the archaeology industry was ill-served and mis-lead by PPG16 and that the future will require different skill-sets and probably different deliverers.

And when i said …..’not the smoking gun it should have been’… i meant that it was a brilliant article that needs a wider audience.

Keep up the excellent work

Much Ass Grassy Ass Amigo.

I don’t think that using a quote from Churchill, to back an argument about the relative merits of differing socio/economic and political systems, adds to an argument. This was a man who, after all, spent time in the Liberal party, was responsible for Gallipoli, refused to negotiate over Indian independence, his views on Ghandi are legend. In addition his main electoral (disastrous) gambit in the 1945 election was to predict that under Labour it would be like living under the Gestapo. A great war leader he may have been, and his tenacity was amazing. His political judgement however was not.

Oh Yes!